Part One of a Four-Part Series:

Unveiling the Story Behind the Heketi's Logo

[Logo above is the upcoming new design for Heketi House, drawing inspiration from Heketi Montessori.]

The word Heketi is a Taino word meaning "One". One Familia, One Comunidad.

The island (Puerto Rico) our people called home was named Boriken by the Tainos. That is why we call ourselves Boricuas. La gente de Borinquen has been dispersed over generations by the moving force of colonialism.

Puerto Rican ways of embodying Indigenous traditions of the Taino have endured, forming the backbone of Puerto Rican culture and identity. More on this another time.

Let's contextualize where I'm from and briefly about my background.

My father was born in San Juan Bayamon, and my mother was born in the lower east side.

Their parents were born in Puerto Rico.

I was born in New York in 1976, which makes me a Nuyorican - Being Puerto Rican runs in my veins—Boricua yo soy.

The sounds of congas and the ritmo of the music playing from a record player while my mother cleaned the house were always fun. The house was loud and vibrant. Sometimes the neighbors upstairs blasted their music that overpowered our music, so my mother would use her broomstick to pound the ceiling while the rollers on her head shook.

I carry this energy with me while I clean and blast my music.

My father was an upholster fixing chairs or sofas for a living.

[Me standing next to my dad, appearing as if I'm about to take a bite out of a wooden chip stick, haha!]

On a hot summer day, he would make morir sonando (Morir sonando means "to die dreaming" in Spanish). My dad took pride in making a slamming morir sonando with orange juice, carnation milk, and some ice for a hot summer day.

My mom was very particular about sweeping the floor. She was on her knees, using a brush to get into corners and sides to bring all the dust and dirt into one area, where she eventually took a broom to finish the rest.

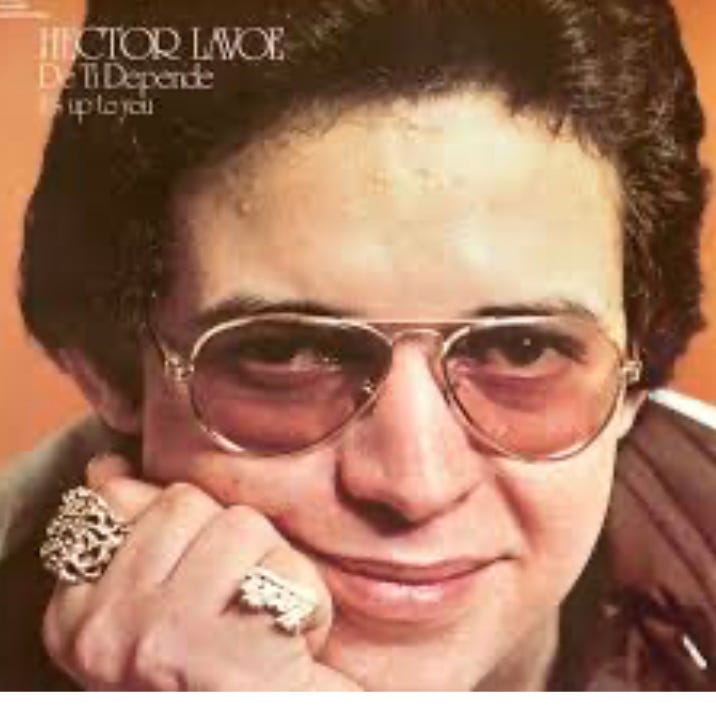

I would watch her place her wet clothes on a drying rack while listening to Hector Lavoe's salsa classic, "Periódico De Ayer," on vinyl.

Folding clothes was eventful. My mom was particular about folding clothes and bedsheets. Her tongue would be out to the side with an intense concentration. The final product was crisp, flat as a pancake, and the crease was always perfectly aligned.

Then there is my mother-in-law's annual tradition of making pasteles with Lela. Each family member circled the table, creating a traditional Christmas Eve dish. For a proper Puerto Rican Christmas, you must have three things on the table- pernil, Arroz con gandules, and pasteles!

My journey continues, and I continue to share my stories through the work of Heketi Montessori because we are storytellers, and representation is critical to affirm.

As children grow and develop their identity is shaped by observing those around them. When children do not see people around them with whom they share similarities such as religion, race, ethnicity, sexuality, and culture, they are more likely to have a harder time developing their sense of identity.1

One of the areas in which I felt deprived of is not knowing my native tongue fluently. It has improved, but my heart sometimes feels heavy because of the WHY I did not develop my native language at an early age.

I was born in 1976, surrounded by Latin music, listened to a family member who spoke Spanish, and was raised to appreciate my culture. However, I was spoken to only in English. That decision was mainly from my father, who lived through difficult times in Puerto Rico and possibly idealized the idea of my brother and me learning English from engrained historical injustices in the 1900s.

When my father passed away in 2002, I reflected on why I did not learn my native tongue. My mother is bilingual, so why. My mom shared that my father felt my brother and I needed to learn English since we live in the U.S.

By 1902, English was the medium of instruction at all levels of education. During this era, Puerto Rico hired U.S. teachers to teach English; soon after, it was mandatory for all teachers to use English as the language of instruction. 2

Here is a poem that I have written that gives me a voice to express my feelings and thoughts.

The poem is called Spanglish.

“Franci aprender a hablar español.”

I heard those words time and time again.

To learn Spanish-my native tongue was

Taught mainly in High School in 1990

But it was forbidden in all public schools

In Puerto Rico, in 1902.

My parents moved to N.Y. in the '70s, a dream for some

Puertorriquenos, and for some,

It was an unfortunate necessity.

In 1976, Born and raised in the Bronx,

Here I am.

“Franci aprender a hablar español."

I asked myself,

Why didn't I acquire fluently a beautiful

Language en mi casita.

My mother spoke two languages, and my dad…one.

For me,

I spoke a language considered the dominant of

All languages.

Papi wanted me to learn English because we spoke only English in America, so he thought when I was little.

As I got older, mi Papi realized

It was a disservice to rid me from la lengua español.

The awakening of my ancestors,

Reaching and revealing what we Boricuas are to

Uphold,

Remember, reclaim, and reconcile with our spoken

Language - Spanish.

Hablamos español in spaces to be known and be seen

Deeper than that

Estamos reclamando las lenguas de los Taínos,

Los Taínos que nosotros somos.

When we use words like

batea- large tray,

bohio- typical round home of Taínos

Boricua- valiant people

jamaica- hammock.

iguana - lizard,

and

Yocahú - God

We are reclamando.

"aprender a hablar español"

Papi, gracias for reminding me every day to learn Spanish.

A beautiful language that you had the privilege of speaking

Until the day you died.

Although logically, you thought it wasn't for me when I was a little girl - a thought stolen from you,

Stripped from the cerebral part of your brain,

Desensitizing the idea of sharing what is ours,

You did not know.

Papi gracias for showing your strength in not learning English

Gracias for still being a voice in my head,

"Aprender a hablar español,"

Papi, yo estoy hablando español y todavía estoy aprendiendo español.

How did it all begin? Searching.

Part of my journey that started this search of nurturing my roots was from a conference called, Embracing Equity in November 2018. Trisha Moquino was one of the presenters. After sharing how my father communicated with me by speaking to my mom in his first and only language, Spanish, my mom would share what he said to me in English. Trisha was empathetic and said, "I hear this story all the time." At that moment, I finally felt like I wasn't alone in this.

Continue reading at my Heketi blog:

In Part Two of Unveiling the Story Behind the Heketi's Logo: "Aprende a hablar español," I delve deeper into the cultural significance and symbolism behind Heketi's logo.

¡Brava! A heartfelt piece! You have serious skills in ethnography- keep cultivating! Combined with linguistics as you do, you wrote a compelling story! I look forward to reading the rest! (